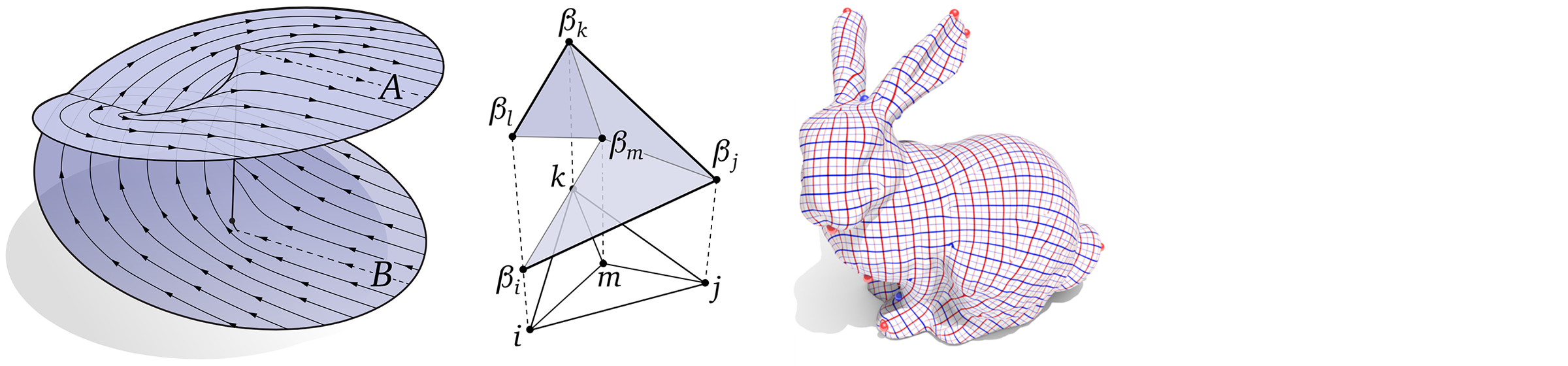

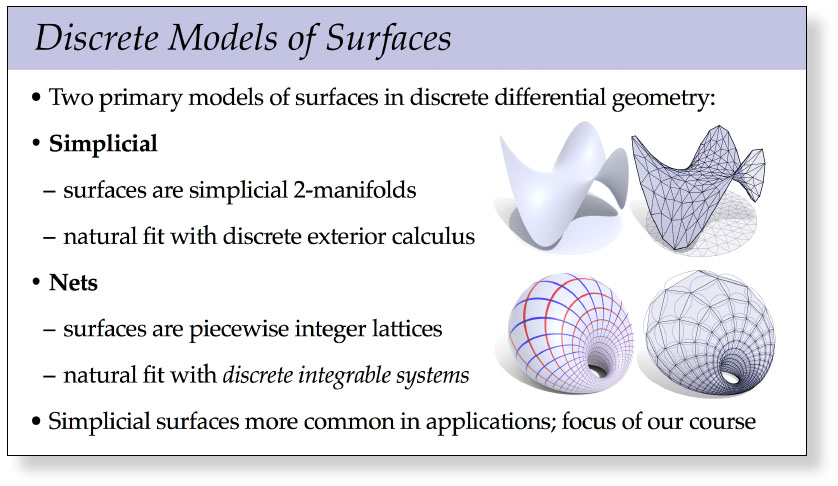

We’ll follow up our lecture on smooth surfaces with a view of surfaces from the discrete point of view. Our goal will be to translate basic concepts (such as the differential, immersions, etc.) into a purely discrete language. Here we’ll also start to see the benefit of developing discrete differential forms: many of the statements we made about surfaces in the smooth setting can be translated into the discrete setting with minimal effort. As we move forward with discrete differential geometry, this “easy translation” will enable us to take advantage of deep insights from differential geometry to develop practical computational algorithms.

Author: Keenan

Lecture 12—Smooth Surfaces

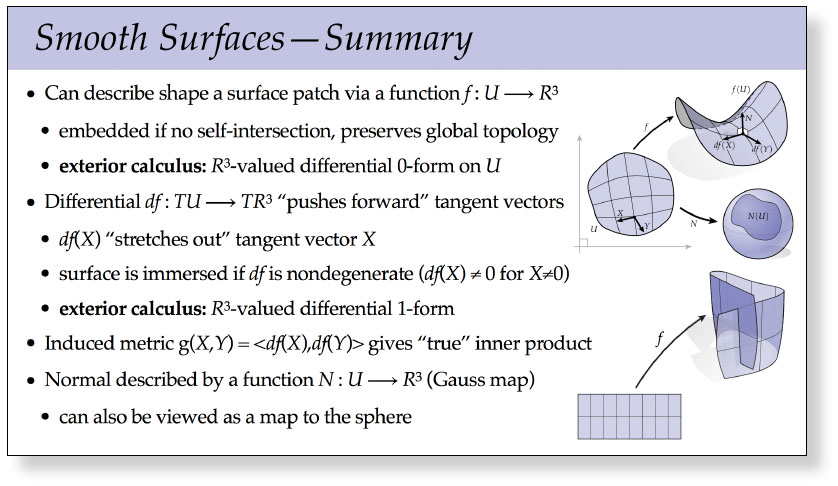

This lecture gives a crash course in the differential geometry of surfaces. There’s of course way more to know about surfaces than we can pack into a single lecture (and we’ll see plenty more later on), but this lecture will cover basic concepts like how to describe a surface and its normals. It also starts to connect surface theory to the other tools we’ve been building up, via vector-valued differential forms.

Reading 5—Curves and Surfaces (due 3/7)

Your next reading complements our in-class discussion of the geometry of curves and surfaces. In particular, you should read Chapter 3 of the course notes, pages 28–44. This reading is due next Thursday, March 7.

Handin instructions are described on the Assignments Page.

Since these notes just barely scratch the surface (literally), I am often asked for recommendations on books that provide a deeper discussion of surfaces. The honest answer is, “I don’t know; I mostly didn’t learn it from a book.” But there are a couple fairly standard references (other) people seem to like, both of which should be available digitally from the CMU library:

Lecture 11—Discrete Curves

This lecture presents the discrete counterpart of the previous lecture on smooth curves. Here we also arrive at a discrete version of the fundamental theorem for plane curves: a discrete curve is completely determined by its discrete parameterization (a.k.a. edge lengths) and its discrete curvature (a.k.a. exterior angles). Can you come up with a discrete version of the fundamental theorem for space curves? If we think of torsion as the rate at which the binormal is changing, then a natural analogue might be to (i) associate a binormal \(B_i\) with each vertex, equal to the normal of the plane containing \(f_{i-1}\), \(f_{i}\), and \(f_{i+1}\), and (ii) associate a torsion \(\tau_{ij}\) to each edge \(ij\), equal to the angle between \(B_i\) and \(B_{i+1}\). Using this data, can you recover a discrete space curve from edge lengths \(\ell_{ij}\), exterior angles \(\kappa_i\) at vertices, and torsions \(\tau_{ij}\) associated with edges? What’s the actual algorithm? (If you find this problem intriguing, leave a comment in the notes! It’s not required for class credit.)

Lecture 10—Smooth Curves

After spending a great deal of time understanding some basic algebraic and analytic tools (exterior algebra and exterior calculus), we’ll finally start talking about geometry in earnest, starting with smooth plane and space curves. Even low-dimensional geometry like curves reveal a lot of the phenomena that arise when studying curved manifolds in general. Our main result for this lecture is the fundamental theorem of space curves, which reveals that (loosely speaking) a curve is entirely determined by its curvatures. Descriptions of geometry in terms of “auxiliary” quantities such as curvature play an important role in computation, since different algorithms may be easier or harder to formulate depending on the quantities or variables used to represent the geometry. Next lecture, for instance, we’ll see some examples of algorithms for curvature flow, which naturally play well with representations based on curvature!

Slides—Discrete Exterior Calculus

This lecture wraps up our discussion of discrete exterior calculus, which will provide the basis for many of the algorithms we’ll develop in this class. Here we’ll encounter the same operations as in the smooth setting (Hodge star, wedge product, exterior derivative, etc.), which in the discrete setting are encoded by simple matrices that translate problems involving differential forms into ordinary linear algebra problems.

Slides—Discrete Differential Forms

In this lecture, we turn smooth differential \(k\)-forms into discrete objects that we can actually compute with. The basic idea is actually quite simple: to capture some information about a differential \(k\)-form, we integrate it over each oriented \(k\)-simplex of a mesh. The resulting values are just ordinary numbers that give us some sense of what the original \(k\)-form must have looked like.

Slides—Exterior Calculus II: Integration

Our first lecture on exterior calculus covered differentiation; our second lecture completes the picture by discussing integration of differential forms. The relationship between integration and differentiation is encapsulated by Stokes’ theorem, which generalizes the fundamental theorem of calculus, as well as many other important theorems from vector calculus and complex analysis (divergence theorem, Green’s theorem, Cauchy’s integral formula, etc.). Stokes’ theorem also plays a key role in numerical discretization of geometric problems, appearing for instance in finite volume methods and boundary element methods; for us it will be the essential tool for developing a discrete version of differential forms that we can actually compute with.

Reading 4: Exterior Calculus — due 2/14

The next reading assignment will wrap up our discussion of exterior calculus, both smooth and discrete. In particular, it will explore how to differentiate and integrate \(k\)-forms, and how an important relationship between differentiation and integration (Stokes’ theorem) enables us to turn derivatives into discrete operations on meshes. In particular, the basic data we will work with in the computational setting are “integrals of derivatives,” which amount to simple scalar quantities we can associate with the vertices, edges, faces, etc. of a simplicial mesh. These tools will provide the basis for the algorithms we’ll explore throughout the rest of the semester.

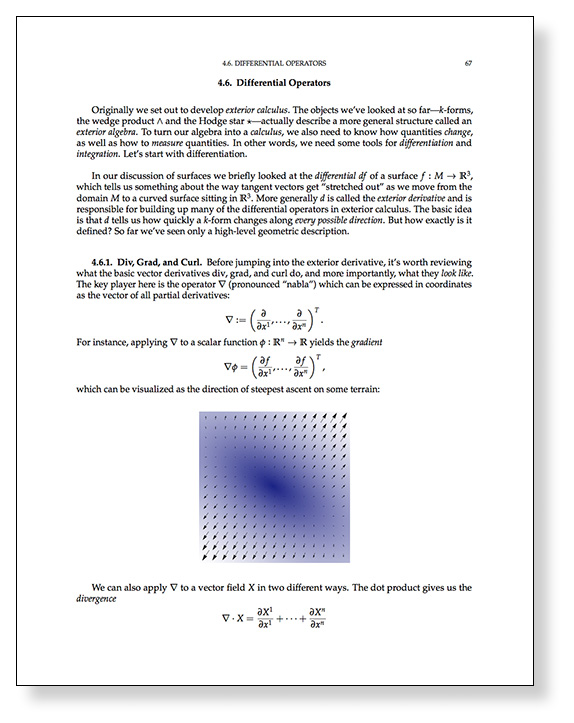

The reading is the remainder of Chapter 4 from the course notes, “A Quick and Dirty Introduction to Exterior Calculus”, Sections 4.6 through 4.8 (pages 67–83). Note that you just have to read these sections; you do not have to do the written exercises; a different set of written problems will be posted later on. The reading is due Thursday, February 14 at 10am. See the assignments page for handin instructions.

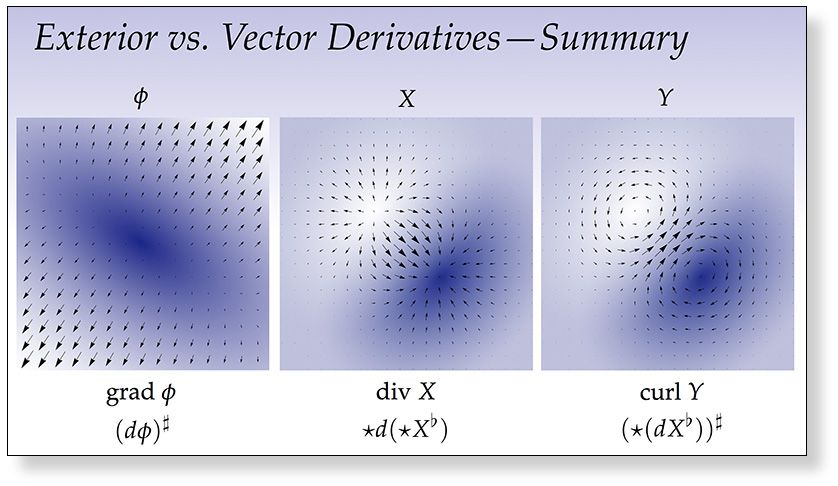

Slides—Exterior Calculus I: Differentiation

Ordinary calculus provides tools for understanding rates of change (via derivatives), total quantities (via integration), and the total change (via the fundamental theorem of calculus). Exterior calculus generalizes these ideas to \(n\)-dimensional quantities that arise throughout geometry and physics. Our first lecture on exterior calculus studies the exterior derivative, which describes the rate of change of a differential form, and (together with the Hodge star) generalizes the gradient, divergence, and curl operators from standard vector calculus.